Phyllis Doyle Burns has given Once Upon a History a marvelous and accurate story about a remarkable woman. Parts of Mary's diary were published in 1905, and after further entries were discovered later on in the century, the diary went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for history in 1982.

Ms. Doyle put her heart and soul into this kind contribution and we here at the Carolinian's Archives can't thank her enough. To me, Mary Chesnut, seems a politically astute, extraordinarily perceptive, Melanie-type woman of the movie Gone With the Wind. A link to Phyllis's excellent site can be found at the end of the article. And so, we begin the story of a woman who's diary is a "vivid picture of a society in the throes of its life & death struggle."

Ms. Doyle put her heart and soul into this kind contribution and we here at the Carolinian's Archives can't thank her enough. To me, Mary Chesnut, seems a politically astute, extraordinarily perceptive, Melanie-type woman of the movie Gone With the Wind. A link to Phyllis's excellent site can be found at the end of the article. And so, we begin the story of a woman who's diary is a "vivid picture of a society in the throes of its life & death struggle."

***image: Mary Boykin Chesnut, wiki pd

Mary Boykin Chesnut, 1823 - 1886

Wikipedia Public Domain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Boykin_Chesnut

In A Diary from Dixie Mary Boykin Chesnut, a politically savvy woman, noted on December 10, 1860, in Charleston, South Carolina when she said to her companions, "A fever that only bloodletting will cure". She was referring to the tensions building up between the North and South political and social factions.

Mary was not a woman to sit calmly outside the boundaries of political talk and rumours, fanning herself and sipping mint juleps - far from it. No, she was right in the midst of the conversations that men dominated. Mary was an intense listener. She paid attention to tone and inflection of voice. She also had a great memory and recorded what she heard. She could catch a conversation a distance away and quickly find out what was going on and who was speaking. Was she eavesdropping or snooping? No - she was alert to the state of her country, what her husband was up against as a high-ranking official, and the way of life in the South, their hopes, fears and uncertainty of what was to come.

Mary was a natural writer and keeper of accurate records, including names and dates. It started with her personal, private diary of daily life among family and friends then exploded into her book A Diary from Dixie, a time-honored masterpiece of life during the war that tore the country, families and friends apart.

The diary was not published till 1905, nineteen years after Mary died. She wrote it in a concise and dynamic style that keeps the reader bound to her time in history. It is still considered by historians as one of the most important documented American Civil War journals ever written. It contains not just narratives of a most crucial time in American history, but personal observations, emotions and thoughts. The diary was one of the most significant books of her time, which is still used today as an accurate resource for history of the Civil War. Mary was a remarkable and resourceful woman who lived at a time of great struggle and change in America.

Mary Boykin Miller was born March 31, 1923 in the High Hills of Santee, a region of long, narrow hills in Sumter County, South Carolina. Her parents were Stephen Decatur Miller of South Carolina and Mary Boykin. Miller served in the United States Congress and was elected as governor of South Carolina in 1829 as a proponent of nullification. In 1831 he became a U.S. Senator. When Miller retired from politics he moved his family to Camden, Mississippi where he purchased three cotton plantations.

The young girl received an excellent education at Mme. Talvande's French School for Young Ladies. She was 13 years old at the time of enrollment, had a sharp mind, she spoke German and French fluently and had a good life. She read a lot and garnered a great knowledge. With her father holding important positions in the military and then politics she was well on her way to becoming politically savvy at an early age.

When Mary was seventeen she married James Chesnut, Jr on April 23, 1840. James was the only surviving son of one of the largest landowners in South Carolina. For the next twenty years Mary and James lived or spent most of their time at Mulberry, the home and one of several plantations owned by James Chesnut, Sr. It is evident how much Mary loved the home and her in-laws from the descriptions she wrote in her diary.

***image: Mulberry Plantation, Chestnut home, wiki pd

Mulberry Plantation, Home of James and Mary Boykin Chesnut

Wikipedia Public Domain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mulberry_Plantation

The Diary ~

Mary took an active part in her husband's career through entertaining, which is an important part of building political networks. She was well-known for her charming hospitality and expertise as a hostess. Like her father, James Chestnut held important offices in the military and politics - he needed a wife like Mary who supported him fully. When the War Between the States was inevitable Mary was very much aware of the vast historical importance of times to come - so, she kept writing.

Mary wrote every day in her diary, regardless of where she was. She was a model woman of the aristocracy yet did not write on just the upper class society. She included all classes of people in her diary and how their lives, too, were affected by the war. She included excerpts of letters from her friends who wrote about important events and persons. Mary had dinner parties often where, before the secession and war, notable people of both the North and South were invited. She wrote about their conversations which had an impact on what was to come. Without knowing exactly what was to come, Mary had vision and knew what statements would become of special note for future reference.

Mary started her diary years before the outbreak of the war and wrote about family, their homes, careers and way of life in her circles. She wrote down the passage of time and lives within family, the endearing love for each other and the sorrows of loss when loved ones died. She also expressed her hopes that slaves would always be treated well and kindly, as her father-in-law did. Mary never liked the idea of slavery, but she kept that to herself. She started writing about the politics and war on February 18, 1861. Her last entry was August 2, 1865.

She had a remarkable understanding of people, their concepts and what honed their thoughts or opinions. It was as if her mind could dive behind the spoken words to the heart of the matter. It came to be known that Mary was not easily shocked or deceived. Voices of men who were experienced and knowledgeable of politics and war did not hush their voices when she entered their groups.

When the possibility of war was talked about in all levels of society she wrote down what she heard from others and included her own thoughts, with wit, charm and frankness. She wrote about her interview with Robert E. Lee and her thoughts about Jefferson Davis. Mary accompanied her husband on his military operations to major southern towns. This gave her the opportunity to speak with southern politicians and hear their stories, private concerns and interests which she included in her book.

When reading what Mary wrote of conversations at one of her many dinner parties with distinguished guests it is like sitting right there at the table hearing it all in person. The candle lights casting glow or shadows on faces, tone of voices, expressions - it all comes alive through Mary's words.

On December 10, 1860 Mary had described how in Camden they were so "busy and frantic with excitement" as Confederate troops drilled and marched in training and parades with their guns, swords, red sashes and high blue cockades. She was very descriptive of people and events, painting vivid pictures with words.

The talk of secession before the outbreak of war is well covered by Mary in the diary. She wrote down word for word what men like Francis W. Pickens, the Governor of South Carolina, said about the upcoming convention that was possibly to end in the vote to secede from the Union.

Eleven days later Mary sat with friends reviewing a copy of the Secession Ordinance. Mrs. Kincaid, who brought the copy, said "God help us. As our day, so shall our strength be." This simple statement was received with gratitude to ease tension in the group.

Mary's pride and respect for the leading politicians and notables of the South comes through strongly in her writing. She relates that South Carolina was splendidly represented, never more so than when they voted to secede with conviction and faith for success. She wrote that it "makes society delightful" and right she was - for the patriotism and excitement of preparing to become their own republic, their own country, sent ecstatic emotions soaring through their veins. Love and pride for being part of the South was strong in their hearts.

Mary took an active part in her husband's career through entertaining, which is an important part of building political networks. She was well-known for her charming hospitality and expertise as a hostess. Like her father, James Chestnut held important offices in the military and politics - he needed a wife like Mary who supported him fully. When the War Between the States was inevitable Mary was very much aware of the vast historical importance of times to come - so, she kept writing.

Mary wrote every day in her diary, regardless of where she was. She was a model woman of the aristocracy yet did not write on just the upper class society. She included all classes of people in her diary and how their lives, too, were affected by the war. She included excerpts of letters from her friends who wrote about important events and persons. Mary had dinner parties often where, before the secession and war, notable people of both the North and South were invited. She wrote about their conversations which had an impact on what was to come. Without knowing exactly what was to come, Mary had vision and knew what statements would become of special note for future reference.

Mary started her diary years before the outbreak of the war and wrote about family, their homes, careers and way of life in her circles. She wrote down the passage of time and lives within family, the endearing love for each other and the sorrows of loss when loved ones died. She also expressed her hopes that slaves would always be treated well and kindly, as her father-in-law did. Mary never liked the idea of slavery, but she kept that to herself. She started writing about the politics and war on February 18, 1861. Her last entry was August 2, 1865.

She had a remarkable understanding of people, their concepts and what honed their thoughts or opinions. It was as if her mind could dive behind the spoken words to the heart of the matter. It came to be known that Mary was not easily shocked or deceived. Voices of men who were experienced and knowledgeable of politics and war did not hush their voices when she entered their groups.

When the possibility of war was talked about in all levels of society she wrote down what she heard from others and included her own thoughts, with wit, charm and frankness. She wrote about her interview with Robert E. Lee and her thoughts about Jefferson Davis. Mary accompanied her husband on his military operations to major southern towns. This gave her the opportunity to speak with southern politicians and hear their stories, private concerns and interests which she included in her book.

When reading what Mary wrote of conversations at one of her many dinner parties with distinguished guests it is like sitting right there at the table hearing it all in person. The candle lights casting glow or shadows on faces, tone of voices, expressions - it all comes alive through Mary's words.

On December 10, 1860 Mary had described how in Camden they were so "busy and frantic with excitement" as Confederate troops drilled and marched in training and parades with their guns, swords, red sashes and high blue cockades. She was very descriptive of people and events, painting vivid pictures with words.

The talk of secession before the outbreak of war is well covered by Mary in the diary. She wrote down word for word what men like Francis W. Pickens, the Governor of South Carolina, said about the upcoming convention that was possibly to end in the vote to secede from the Union.

Eleven days later Mary sat with friends reviewing a copy of the Secession Ordinance. Mrs. Kincaid, who brought the copy, said "God help us. As our day, so shall our strength be." This simple statement was received with gratitude to ease tension in the group.

Mary's pride and respect for the leading politicians and notables of the South comes through strongly in her writing. She relates that South Carolina was splendidly represented, never more so than when they voted to secede with conviction and faith for success. She wrote that it "makes society delightful" and right she was - for the patriotism and excitement of preparing to become their own republic, their own country, sent ecstatic emotions soaring through their veins. Love and pride for being part of the South was strong in their hearts.

Life after secession

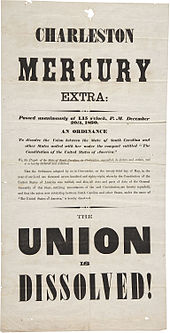

South Carolina Secession Delegation, 1860

"We the people of the State of South Carolina, in Convention assembled do declare and ordain, and it is hereby declared and ordained, That the Ordinance adopted by us in Convention, on the twenty-third day of May in the year of our Lord One Thousand Seven hundred and eighty eight, whereby the Constitution of the United State of America was ratified, and also all Acts and parts of Acts of the General Assembly of this State, ratifying amendment of the said Constitution, are hereby repealed; and that the union now subsisting between South Carolina and other States, under the name of The United States of America, is hereby dissolved."

In February 1861, Jefferson Davis was elected President of the Confederacy and Alexander H. Stephens, statesman of Georgia, became Vice President.

Mary notes how her relationship with Mrs. Varina Jefferson Davis had changed. With a warm greeting to each other they then abstained from talk of politics and things said in their respective circles. Visiting the First Lady had become quite different than when visiting "Jeff's" wife before the secession.

Interesting anecdotes and mention of important men in society and politics is disbursed throughout the diary. Mary's wit and personal comments slip out with her private thoughts about what one person or another said or did, such as, "What did he know? He only thought, he did not feel." Her thoughts about a slave on the auction block makes her faint and feeling ill. "Poor women, poor slaves!"

Newspaper headlines and short excerpts of articles are recorded in the diary. Men in high offices began to resign positions held in United States government to join the side of their Southern neighbors and states. Soldiers resigned their commissions from the Union Army and came to James Chestnut requesting an office. A slave who was once proud of his important position in a wealthy family had been cast aside and became ragged and forlorn, homeless.

Slowly the reader begins to see subtle changes to life in the South after the Secession. Then it explodes into the actual war and how life in the South is devastated.

Some of the things Mary records may be a bit shocking to some, for she was noting the personal side of the Civil War era. We read about history of the battles and leaders, but rarely do we get to read about the down-to-earth and bold statements of people in daily life. Mary relates how life was for the South during the war. Phenomenal changes had occurred to their way of life.

The appreciation for the most simple things had grown to amazing proportions. The cost of necessities rose to staggering, unheard of prices. Shoes of comfort and style were a thing of the past. A pair of simple shoes and socks to keep feet warm was a cherished treasure. Always somewhere would be a gathering of women to knit socks for the soldiers who would go without if not for those dedicated women. Mary often joined the knitting groups. Busy skilled hands that once made delicate, intricate and lovely items in leisure time had become necessary tools for much needed things that had become scarce.

What flowed through the minds of women as they sat and knitted for their soldiers? What went through the minds of soldiers fighting for their country and families? Mary expresses many of these thoughts which helps us to understand how life was during the war.

To write more about this would only take away from the pleasure of reading Mary's accounts written in her detailed and descriptive style. Mary did not focus much on the battles and campaigns as plethora of authors did and still do. Her diary is about people, their daily lives, concerns and involvement, their fears and hopes. From the first rumours of issues between the North and South, the secession, the war and the reconstruction, Mary kept accurate accounts of the political / military people involved and what was happening in personal lives.

Taking of the forts and arsenals ~

The Confederacy needed to strengthen their positions in light of upcoming battles that were no longer just probable, but inevitable. They had to seize the forts and arsenals in the South.

Fort Sumter was one of the strongest of the United States Army. The South must take it as their own was the talk and Mary writes down the significant details. The U.S. Army was vulnerable to an attack where they were stationed in Charleston harbor. On December 26th Robert Anderson, Major of the First Artillery, moved his command to Fort Sumter to better prepare for defense against the Confederacy. More Southern states had joined the Confederacy and their strength was growing. Fort Pickens was another strong one the Confederacy had to take if at all possible.

Attack against Fort Sumter - 1861

A Currier and Ives print

Wikipedia Public Domain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Fort_Sumter

Mary writes passionately of how the political intrigue in the South had become "as rife as in Washington" and her thoughts on what the South needs to do. Born leaders were needed to meet the tremendous odds, endurance of the toughest with military instinct, were thoughts running through her head.

Because Mary was married to Brigadier General of the Confederate Army, James Chesnut, she was right in the midst of all the events leading up to and during the war. Her personal thoughts of men who became historical figures show the reader that these were real life people, each with their own concerns, abilities and goals.

Her diary brings us closer to Lincoln, Davis, Pickens, high ranking military officers like her husband, governors and senators who had major responsibilities, and enlisted soldiers. We, as readers, find simple statements from President Lincoln and others rather than reading famous speeches that we learned in history lessons and may know by heart. Mary gives us an insider's view of notables and people of society she knew. It is incredible to know what went on in daily life and who said what. We easily become acquainted with these historical figures because Mary was so dedicated in documenting conversations and events. She had the foresight that the future would want to read such remarkable accounts of those times of struggle and uncertainty.

The Confederacy needed to strengthen their positions in light of upcoming battles that were no longer just probable, but inevitable. They had to seize the forts and arsenals in the South.

Fort Sumter was one of the strongest of the United States Army. The South must take it as their own was the talk and Mary writes down the significant details. The U.S. Army was vulnerable to an attack where they were stationed in Charleston harbor. On December 26th Robert Anderson, Major of the First Artillery, moved his command to Fort Sumter to better prepare for defense against the Confederacy. More Southern states had joined the Confederacy and their strength was growing. Fort Pickens was another strong one the Confederacy had to take if at all possible.

Attack against Fort Sumter - 1861

A Currier and Ives print

Wikipedia Public Domain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Fort_Sumter

Mary writes passionately of how the political intrigue in the South had become "as rife as in Washington" and her thoughts on what the South needs to do. Born leaders were needed to meet the tremendous odds, endurance of the toughest with military instinct, were thoughts running through her head.

Because Mary was married to Brigadier General of the Confederate Army, James Chesnut, she was right in the midst of all the events leading up to and during the war. Her personal thoughts of men who became historical figures show the reader that these were real life people, each with their own concerns, abilities and goals.

Her diary brings us closer to Lincoln, Davis, Pickens, high ranking military officers like her husband, governors and senators who had major responsibilities, and enlisted soldiers. We, as readers, find simple statements from President Lincoln and others rather than reading famous speeches that we learned in history lessons and may know by heart. Mary gives us an insider's view of notables and people of society she knew. It is incredible to know what went on in daily life and who said what. We easily become acquainted with these historical figures because Mary was so dedicated in documenting conversations and events. She had the foresight that the future would want to read such remarkable accounts of those times of struggle and uncertainty.

Letter to Mary ~

In a letter from James Chestnut to Mary, dated June 29, 1862, from Richmond, Virginia, he writes about "the largest and fiercest (battle) of the whole war".

Some research to find out what day of the week Chestnut wrote the letter, which was a Sunday, then tracking back to a list of battles, I found the Friday and battle he was referring to: Battle of Gaines Mill (or Battle of Chickahominy), on Friday June 27, 1862. On that day, Robert E. Lee's force launched the largest Confederate attack of the war, about 60,000 men in six divisions. The Union forces retreated across the Chickahominy River. The fierce battle saved Richmond for the Confederacy.

In a letter from James Chestnut to Mary, dated June 29, 1862, from Richmond, Virginia, he writes about "the largest and fiercest (battle) of the whole war".

Some research to find out what day of the week Chestnut wrote the letter, which was a Sunday, then tracking back to a list of battles, I found the Friday and battle he was referring to: Battle of Gaines Mill (or Battle of Chickahominy), on Friday June 27, 1862. On that day, Robert E. Lee's force launched the largest Confederate attack of the war, about 60,000 men in six divisions. The Union forces retreated across the Chickahominy River. The fierce battle saved Richmond for the Confederacy.

***image: Battle of Gaines Mill, wiki pd

"Battle of Gaines Mill, Valley of the Chickahominy, Virginia, June 27, 1862." Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 - 1985.

Wikipedia Public Domain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Gaines's_Mill

After the war ~

After the war the South faced Reconstruction and the difficulty of re-joining the Union. Re-building their homelands was yet another tremendous struggle. So much had been damaged, so much destroyed and lost forever, so many people had died. Of the 750,000 to 1,000,000 enlisted soldiers of the Army, Marines and Navy in the Confederacy, 290,000 were killed in battle or died in Union prisons. The Union lost more soldiers than the South did - they had over 2 million soldiers enlisted. Both sides lost so much.

And although these were the official estimates for almost 140 years, recent revised historians estimates of fatalities, North and South, place these numbers at possibly as high as, or close to, 800,000. Which, of course, means many more soldiers died in the terrible conflict than had long been previously thought. To put things in perspective, total deaths for U.S. soldiers in WW2 was about 405,000 men, at a time when the population of the country was very much higher than the early 1860s.

After the war the South faced Reconstruction and the difficulty of re-joining the Union. Re-building their homelands was yet another tremendous struggle. So much had been damaged, so much destroyed and lost forever, so many people had died. Of the 750,000 to 1,000,000 enlisted soldiers of the Army, Marines and Navy in the Confederacy, 290,000 were killed in battle or died in Union prisons. The Union lost more soldiers than the South did - they had over 2 million soldiers enlisted. Both sides lost so much.

And although these were the official estimates for almost 140 years, recent revised historians estimates of fatalities, North and South, place these numbers at possibly as high as, or close to, 800,000. Which, of course, means many more soldiers died in the terrible conflict than had long been previously thought. To put things in perspective, total deaths for U.S. soldiers in WW2 was about 405,000 men, at a time when the population of the country was very much higher than the early 1860s.

Southern women during the Civil War ~

Mary Boykin Chesnut gave us a vivid image of the women in her time by writing about their emotions, fears, patriotism, opinions, how involved they had become and how much aware they were of the politics and battles of the war, how they suffered deep emotions and fears.

They were dedicated to The Southern Cause, supportive to each other and to their husbands, fathers and sons who were so far away. They kept an extremely active schedule during the days attending meetings, volunteering for anything that would help the Confederacy, and keeping everything at home running as smoothly as possible. One can imagine how these women and thousands of others spent the long lonely nights alone with their personal thoughts, emotions, hopes, and prayers.

It is very probable that most women, regardless of their station in life, must have written in personal diaries. To be able to read just one is so enlightening about a time in the distant past. Reading Mary's diary brings it all back in a new light.

The South lost the war and their way of life changed drastically, yet they never lost that Southern spiritual passion for their homelands, their souls were never conquered, and their hospitality is still as warm as it always has been.

"August 2d. - Dr. Boykin and John Witherspoon were talking of a nation in mourning, of blood poured out like rain on the battlefields-for what? "Never let me hear that the blood of the brave has been shed in vain! No; it sends a cry down through all time.""

- Mary Boykin Chesnut, 1865

Mary Boykin Chesnut gave us a vivid image of the women in her time by writing about their emotions, fears, patriotism, opinions, how involved they had become and how much aware they were of the politics and battles of the war, how they suffered deep emotions and fears.

They were dedicated to The Southern Cause, supportive to each other and to their husbands, fathers and sons who were so far away. They kept an extremely active schedule during the days attending meetings, volunteering for anything that would help the Confederacy, and keeping everything at home running as smoothly as possible. One can imagine how these women and thousands of others spent the long lonely nights alone with their personal thoughts, emotions, hopes, and prayers.

It is very probable that most women, regardless of their station in life, must have written in personal diaries. To be able to read just one is so enlightening about a time in the distant past. Reading Mary's diary brings it all back in a new light.

The South lost the war and their way of life changed drastically, yet they never lost that Southern spiritual passion for their homelands, their souls were never conquered, and their hospitality is still as warm as it always has been.

"August 2d. - Dr. Boykin and John Witherspoon were talking of a nation in mourning, of blood poured out like rain on the battlefields-for what? "Never let me hear that the blood of the brave has been shed in vain! No; it sends a cry down through all time.""

- Mary Boykin Chesnut, 1865

Note from author ~

Mary was a fantastic writer, she will make you laugh, ponder, cheer, cry, and bring the era of her times to life. She described things in great detail and kept photos of notable people of her time as well as family members. There is an entire collection of Mary's diary and photographs at the Caroliniana Library in South Carolina. The collection of photographs and a caption for each one is astounding - Generals of the Confederacy and other distinguished men are included. Photos never before seen is amazing to look at. To see the collection is to bring it all back from long ago memories.

The Civil War changed people of the South in many ways. It made some kinder, some bitter. There was another side to slavery that the North did not understand and few people today understand. In some wealthy families who owned slaves there was a bond built from many years of trust, support, nurturing and love. When that bond was torn apart it was heartbreaking for many people.

When traveling to a safer place a woman of the aristocracy and a slave woman to sit close to each other for comfort and security, to give each other a touch on the arm for reassurance, to cry together as friends was not frowned upon. For women to give up their seats on the train for a wounded soldier standing in the aisle did not cause shock, for it was no longer breaking societal customs. A woman and her slave crying together because they would soon be parted due to emancipation was a sorrowful experience. For some bonds people, to suddenly be set free after spending a whole life with one family in the only home they knew was fearful and uncertain. Some southern women could no longer face life because their husband and for many their sons, also, were killed -a goodly number just retreated into darkness and died from broken hearts.

Mary's diary is about people, their sorrows, fears, loss and facing a different way of life, not just the aristocracy, but the bonds people, free blacks, poor whites and just plain regular white folk also. One may very well have a different outlook at the way of life in the South before the Civil War after reading Mary's diary.

http://hubpages.com/@phyllisdoyle

Phyllis Doyle Burns

Mary was a fantastic writer, she will make you laugh, ponder, cheer, cry, and bring the era of her times to life. She described things in great detail and kept photos of notable people of her time as well as family members. There is an entire collection of Mary's diary and photographs at the Caroliniana Library in South Carolina. The collection of photographs and a caption for each one is astounding - Generals of the Confederacy and other distinguished men are included. Photos never before seen is amazing to look at. To see the collection is to bring it all back from long ago memories.

The Civil War changed people of the South in many ways. It made some kinder, some bitter. There was another side to slavery that the North did not understand and few people today understand. In some wealthy families who owned slaves there was a bond built from many years of trust, support, nurturing and love. When that bond was torn apart it was heartbreaking for many people.

When traveling to a safer place a woman of the aristocracy and a slave woman to sit close to each other for comfort and security, to give each other a touch on the arm for reassurance, to cry together as friends was not frowned upon. For women to give up their seats on the train for a wounded soldier standing in the aisle did not cause shock, for it was no longer breaking societal customs. A woman and her slave crying together because they would soon be parted due to emancipation was a sorrowful experience. For some bonds people, to suddenly be set free after spending a whole life with one family in the only home they knew was fearful and uncertain. Some southern women could no longer face life because their husband and for many their sons, also, were killed -a goodly number just retreated into darkness and died from broken hearts.

Mary's diary is about people, their sorrows, fears, loss and facing a different way of life, not just the aristocracy, but the bonds people, free blacks, poor whites and just plain regular white folk also. One may very well have a different outlook at the way of life in the South before the Civil War after reading Mary's diary.

http://hubpages.com/@phyllisdoyle

Phyllis Doyle Burns

RSS Feed

RSS Feed