The first time Randy Godwin really came to my attention was about two years ago, when judging a writing contest. I came upon Randy's submission, that was a story set in Georgia's Okefenokee swamp, and was a taut semi-fiction piece about an ancestor of his who was a lawman on the trail of some no-gooders that climaxed in the midst of that deadly abode.

In any event I thought it one of the best submissions I had perused out of about a thousand read entries. As a matter of fact I gave it third place overall, and Randy may be learning this fact for the first time right here.

After the contest I started reading more of Randy's work and we became friends. It can truly be stated that Randy is of a vanishing breed called the True Southern Gentleman. He comes from a part of Georgia were a man's word and handshake still stand for something. By the way, Randy is also married to a lovely lady named Beth, who keeps him in line on the rare occasions it becomes necessary, so she says.

In any event I thought it one of the best submissions I had perused out of about a thousand read entries. As a matter of fact I gave it third place overall, and Randy may be learning this fact for the first time right here.

After the contest I started reading more of Randy's work and we became friends. It can truly be stated that Randy is of a vanishing breed called the True Southern Gentleman. He comes from a part of Georgia were a man's word and handshake still stand for something. By the way, Randy is also married to a lovely lady named Beth, who keeps him in line on the rare occasions it becomes necessary, so she says.

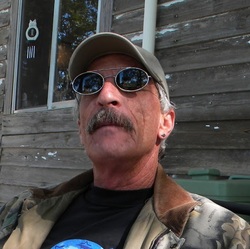

Author, Randy Godwin

Author, Randy Godwin Randy's family goes back many, many generations on their farm and property. He is an excellent writer of the Old South in Georgia and elsewhere. He is also in a unique position with his stories, as he often mixes fact with fiction, with his own outstanding tales from the region. So, in so many words he often writes semi-fiction that delivers a story a reader will be unlikely to forget.

With that, dear readers of the Carolinian's Archives, it is my humble pleasure to introduce you to the first guest post of Randy's here. It seemed an excellent companion to a Civil War story honoring the 150th anniversary of Gettysburg; in which Randy's brother usually participates as a re-enactor, and did participate this year of 2013.

By the way friends, Randy Godwin at Hubpages.com has a fantastic variety of stories covering many subjects such as his awesome collection of S Georgia Amerindian artifacts and the mysterious "Carolina Bays" that cover the SE from his area to the Carolinas.

With that, dear readers of the Carolinian's Archives, it is my humble pleasure to introduce you to the first guest post of Randy's here. It seemed an excellent companion to a Civil War story honoring the 150th anniversary of Gettysburg; in which Randy's brother usually participates as a re-enactor, and did participate this year of 2013.

By the way friends, Randy Godwin at Hubpages.com has a fantastic variety of stories covering many subjects such as his awesome collection of S Georgia Amerindian artifacts and the mysterious "Carolina Bays" that cover the SE from his area to the Carolinas.

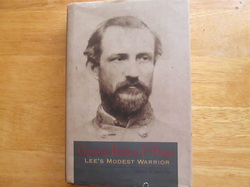

Images of Valor Dying, by Randy Godwin

My chosen profession has become a burden to me now. What was once an exciting and wondrous delving into the art of photography has quickly become a morbid obsession. Gerald Baxter is my professional name. A name once held in mediocre esteem by my fellow travelers, but of late has become a symbol for a type of ghoul or specter of doom.

I cannot blame them though, cannot feel any animosity for their looks of distaste thrown my way when I erect my equipment of light gathering. I am not their enemy, but still they shake their heads as I approach them as if a mere word to them would seal their fate, would forecast a certain death captured for all to see back home where they lived. No, they have the right to think so, these poor lads in arms.

Especially after today they may believe I am somehow responsible for their fate, somehow complicit in the whole disaster of trying to route the Rebs from behind the old stone wall below Marye’s Height. I’d prepared my glass plates with care early that morning and finally, after the fog lifted around ten, used them all. And yes indeed, I captured the faces of dead men, caught their last smiles and tears before they took the deadly walk towards the confederate lines.

I cannot blame them though, cannot feel any animosity for their looks of distaste thrown my way when I erect my equipment of light gathering. I am not their enemy, but still they shake their heads as I approach them as if a mere word to them would seal their fate, would forecast a certain death captured for all to see back home where they lived. No, they have the right to think so, these poor lads in arms.

Especially after today they may believe I am somehow responsible for their fate, somehow complicit in the whole disaster of trying to route the Rebs from behind the old stone wall below Marye’s Height. I’d prepared my glass plates with care early that morning and finally, after the fog lifted around ten, used them all. And yes indeed, I captured the faces of dead men, caught their last smiles and tears before they took the deadly walk towards the confederate lines.

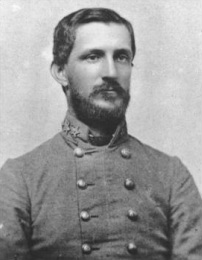

Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman

Acts of Mortal Gods

I must admit to there being a certain feeling of godlike ability, a sense of control despite there being none at all. The mere magic of burning a likeness of a future dead man into a glass plate seems somehow wrong now. But I must do it again. Someone has to do it. It is one of those things we have no control over, one of the events in our lives which seems hell-bound and meant-to-be. You know what I mean, certainly you do.

Somehow it doesn’t seem like war to me, and I suppose it really isn’t. Sure, I could catch a stray bullet, or perhaps an artillery round could go awry, but there is always a chance of death in our short lives no matter the circumstance. I cannot see myself dying near the scene of a battle, but I suppose it could happen easily enough.

I never dreamed when I was serving an apprenticeship to the famous photographer, Matthew Brady, that I would be here now, making visual records of this sad American struggle. I never thought we would actually do it, would kill our fellow citizens, all for such silly reasons.

For what?

My job is not to figure the why of it, but to simply get it down on glass. Somehow it seems shameful for it to be, so I cannot say different now.

Somehow it doesn’t seem like war to me, and I suppose it really isn’t. Sure, I could catch a stray bullet, or perhaps an artillery round could go awry, but there is always a chance of death in our short lives no matter the circumstance. I cannot see myself dying near the scene of a battle, but I suppose it could happen easily enough.

I never dreamed when I was serving an apprenticeship to the famous photographer, Matthew Brady, that I would be here now, making visual records of this sad American struggle. I never thought we would actually do it, would kill our fellow citizens, all for such silly reasons.

For what?

My job is not to figure the why of it, but to simply get it down on glass. Somehow it seems shameful for it to be, so I cannot say different now.

Burning the Glass

No, this is my job and I’ll do it as best I can; will burn the images of time into inanimate plates of former sand crystals and immortalize those who paid the ultimate price. As I said, someone has to do it. I move the horse drawn wagon containing my photography equipment from battle to battle, over rough roads and often through the fields of the local farmers.

They sometimes give me vegetables from their gardens or perhaps even a chicken or smoked ham in exchange for taking pictures of their family members. They too gaze in wonder at me, as if I am indeed somehow special to this angry world. But special I do not feel, not at all my friends.

Sometimes I meet with my peers, other men much like myself, living their lives while they record the demise of other not-so-fortunate warriors. Their guilt at such is similar to mine. I can see it in their eyes too; can tell it from their words and actions, even the way they move slowly about their tasks tell a tale of dread and misgiving.

They sometimes give me vegetables from their gardens or perhaps even a chicken or smoked ham in exchange for taking pictures of their family members. They too gaze in wonder at me, as if I am indeed somehow special to this angry world. But special I do not feel, not at all my friends.

Sometimes I meet with my peers, other men much like myself, living their lives while they record the demise of other not-so-fortunate warriors. Their guilt at such is similar to mine. I can see it in their eyes too; can tell it from their words and actions, even the way they move slowly about their tasks tell a tale of dread and misgiving.

Waiting to Bury the Dead and Gaining Ground to Rest In ...

The dead claim no sides in this battle. They are beyond any glory and honor, if there is such in this war. They lie still upon the battlefield until the often former slaves rush in to pick them up and deposit their remains into some cold, lonely hole, often in the very earth they have fought so desperately for. They have this spot of turf for their eternal resting place as if this was the original plan before the battle began.

I wonder will my work actually make a difference in the lives of those who will eventually lay eyes upon the long dead warriors. It is hard to look a upon these colorful scenes through the camera lens and imagine the picture as it turns out in shades of gray, black, and white long after the battle is over. It’s almost as if the drabness of the finished product somehow purposely needs the cold gray light to lend sobriety to the scenes of war. And, perhaps, it does.

So off I go, setting up my camera, finding a spot to work unencumbered with danger or guilt, of not being a main character in this unhappy charade. No, it isn't an easy job to remain so detached from the conflict, but then, there are always such men attached to these wars.

Those who make the important decisions to attack or defend are often in same situation. I cannot but wonder if those men had to fight their own battles if there would ever be any. Somehow I think not.

I wonder will my work actually make a difference in the lives of those who will eventually lay eyes upon the long dead warriors. It is hard to look a upon these colorful scenes through the camera lens and imagine the picture as it turns out in shades of gray, black, and white long after the battle is over. It’s almost as if the drabness of the finished product somehow purposely needs the cold gray light to lend sobriety to the scenes of war. And, perhaps, it does.

So off I go, setting up my camera, finding a spot to work unencumbered with danger or guilt, of not being a main character in this unhappy charade. No, it isn't an easy job to remain so detached from the conflict, but then, there are always such men attached to these wars.

Those who make the important decisions to attack or defend are often in same situation. I cannot but wonder if those men had to fight their own battles if there would ever be any. Somehow I think not.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed