It is the same in love as in war ;

a fortress that parleys is half taken.

Marguerite de Valois

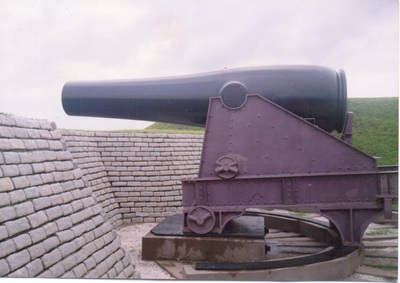

The first thing one may notice on coming into view of St. Augustine's fortress is its low-slung appearance against the skyline. As you get closer, though, you suddenly realize what a mighty stronghold the Castillo de San Marcos truly was...and is.

In fact, the picture to the left reminds me of some kind of Noah's Ark constructed out of stone. Anyway, the fort has proved just as indestructible over the many centuries as that Old Testament miracle-boat was written to be. Maybe the reader will see something else entirely different in this photo of the second-oldest masonry fort in North America, one in San Juan, Puerto Rico, being older.

On approaching the structure it looks to be entirely built by slabs of mollusca, you can even see that these mollusk shells are fused together- and by their own lime secretions at that. This made the walls generally self-absorbing to cannonballs rather than have them explode on impact.

As impressive as the outside of the castle is, the inside promises to hold wonders too.

a fortress that parleys is half taken.

Marguerite de Valois

The first thing one may notice on coming into view of St. Augustine's fortress is its low-slung appearance against the skyline. As you get closer, though, you suddenly realize what a mighty stronghold the Castillo de San Marcos truly was...and is.

In fact, the picture to the left reminds me of some kind of Noah's Ark constructed out of stone. Anyway, the fort has proved just as indestructible over the many centuries as that Old Testament miracle-boat was written to be. Maybe the reader will see something else entirely different in this photo of the second-oldest masonry fort in North America, one in San Juan, Puerto Rico, being older.

On approaching the structure it looks to be entirely built by slabs of mollusca, you can even see that these mollusk shells are fused together- and by their own lime secretions at that. This made the walls generally self-absorbing to cannonballs rather than have them explode on impact.

As impressive as the outside of the castle is, the inside promises to hold wonders too.

IN THE BEGINNING

St. Augustine, Florida was founded in 1565 by one Pedro Menendez de Aviles, a staunch Catholic. The Spanish asserted an exclusive title over La Florida, so when a group of Huguenot French, seeking freedom from persecution back in France, built Fort Caroline down the coast from where St. Augustine would soon be founded, the Spanish commander attacked and killed most of its unwary inhabitants.

On approaching the fort, the French demanded his name and objective. "I am Menendez of Spain," was his reply, "I am sent with strict orders from my king, to gibbet and behead all the Protestants in these regions. The Frenchman who is a Catholic I will spare, -- every heretic shall die." And so they did, these Huguenot men, women and children.

The stronghold's construction was begun in 1672, not long after English buccaneer Robert Searle sacked the presidio of the town in 1668. These fortified base's were built to protect against enemies such as hostile Native Americans, the close-by English settlements in Virginia and Carolina, and above all, pirates like Searle. This swashbuckler's devastating raid convinced the Spanish authorities of the need for something stronger, hence the castle fortress, which was essentially completed twenty-three years after its start.

On approaching the fort, the French demanded his name and objective. "I am Menendez of Spain," was his reply, "I am sent with strict orders from my king, to gibbet and behead all the Protestants in these regions. The Frenchman who is a Catholic I will spare, -- every heretic shall die." And so they did, these Huguenot men, women and children.

The stronghold's construction was begun in 1672, not long after English buccaneer Robert Searle sacked the presidio of the town in 1668. These fortified base's were built to protect against enemies such as hostile Native Americans, the close-by English settlements in Virginia and Carolina, and above all, pirates like Searle. This swashbuckler's devastating raid convinced the Spanish authorities of the need for something stronger, hence the castle fortress, which was essentially completed twenty-three years after its start.

TWO SIEGES IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

During what's called the "first Spanish period" the fort was bombarded twice: in 1702 by James Moore and, in 1740, by Georgia's governor James Oglethorpe. The Spanish in Florida were at the time hereditary enemies of the English in the New World and Moore took advantage of this fact during Queen Anne's War to command an attack on St. Augustine and its fort.

After assembling a force at Charles Town and Port Royal, S.C., with flatteries and dreams of booty, Moore sailed for St. Augustine with a small fleet while another group marched overland. Upon their arrival, the town was ravaged and the fortress closely invested, but without achieving anything of import. His cannon could make no impression on the elastic castle walls, so Moore sent off a Colonel Daniel to Jamaica for pieces of a stronger caliber. But, during his absence, a Spanish fleet entered the mouth of the harbor, forcing Governor Moore to raise the siege and depart, and quickly at that. More of a skedaddle than retreat, in fact.

In 1739 the War of Jenkin's Ear commenced between Great Britain and Spain. This initial conflict later segued into the War of the Austrian Succession. In the intervening years between Moore's expedition and the start of hostilities in 1739, St. Augustine, its castle and environs, had been places of refuge for escaped African American bonds people, some indentured white folk, defeated Amerindian warriors and other downtrodden.

The Creeks, sometimes, and the South Carolinian Yamasees, often, attacked weaker tribes they mostly sold to southern Caribbean sugar plantations or incorporated into their own villages. They also used Northern Florida and the stronghold as bases for raiding the English settlements in the Georgia regions and Carolina after the devastating Yamasee War destroyed that tribe's alliance with the English.

That conflict nearly saw Charleston, SC, captured, devastated and burned ; no doubt after much booty, prisoners and scalps had been taken. But, Governor Craven proved equal to the emergency and after hard fighting drove the Yamasee across the Savannah River where they dispersed. Some of these defeated warriors found a refuge in the Castillo where they were treated with sympathy, for a while, until they became bothersome to the don for a variety of reasons and were expelled to their fate.

In consequence of these situations over time, the great martial reputation of Georgia's governor, James Oglethorpe, that was held by the Crown, indicated this man as the proper person to lead an army from his province and the Carolinas against the Spanish in Florida. The old 42nd regiment of foot from Britain and a strong allied Native American contingent, estimated at over a thousand braves, were included in his force of English and colonial soldiers.

With well over two thousand men Oglethorpe descended on north-east Florida, capturing several smaller forts before laying siege to the Castillo de San Marcos itself. On arriving at the fortress, a message was sent to it,

demanding its surrender, only to be returned by the bastion's confident don, who told Oglethorpe he'd be glad to shake his hand inside the castle, if he could make in that is.

An intense bombardment of the place availed Oglethorpe nothing. In addition, his Native American contingent deserted after he called them "barbarous dogs" for proudly bringing him an enemy scalp. Also, the Castillo's commander, during the lengthy exchange of fierce hot shot over many days, sent forth a band of African American militia and Spanish regulars to re-take the first free black settlement in America, Fort Mose. In this they were successful, after a brief but savage firefight against its surprised but battling Scots Highlander garrison from Darien, Georgia.

With these set-backs and his reluctance to storm the seemingly impregnable walls of the fort, having little faith left in the espirit de corps of his colonial soldiers, General Oglethorpe was left no choice but to raise the siege and ignominiously retreat back to Georgia. There he was regaled for his shortcomings on the campaign but has since been redeemed by some historians over the failed expedition.

After assembling a force at Charles Town and Port Royal, S.C., with flatteries and dreams of booty, Moore sailed for St. Augustine with a small fleet while another group marched overland. Upon their arrival, the town was ravaged and the fortress closely invested, but without achieving anything of import. His cannon could make no impression on the elastic castle walls, so Moore sent off a Colonel Daniel to Jamaica for pieces of a stronger caliber. But, during his absence, a Spanish fleet entered the mouth of the harbor, forcing Governor Moore to raise the siege and depart, and quickly at that. More of a skedaddle than retreat, in fact.

In 1739 the War of Jenkin's Ear commenced between Great Britain and Spain. This initial conflict later segued into the War of the Austrian Succession. In the intervening years between Moore's expedition and the start of hostilities in 1739, St. Augustine, its castle and environs, had been places of refuge for escaped African American bonds people, some indentured white folk, defeated Amerindian warriors and other downtrodden.

The Creeks, sometimes, and the South Carolinian Yamasees, often, attacked weaker tribes they mostly sold to southern Caribbean sugar plantations or incorporated into their own villages. They also used Northern Florida and the stronghold as bases for raiding the English settlements in the Georgia regions and Carolina after the devastating Yamasee War destroyed that tribe's alliance with the English.

That conflict nearly saw Charleston, SC, captured, devastated and burned ; no doubt after much booty, prisoners and scalps had been taken. But, Governor Craven proved equal to the emergency and after hard fighting drove the Yamasee across the Savannah River where they dispersed. Some of these defeated warriors found a refuge in the Castillo where they were treated with sympathy, for a while, until they became bothersome to the don for a variety of reasons and were expelled to their fate.

In consequence of these situations over time, the great martial reputation of Georgia's governor, James Oglethorpe, that was held by the Crown, indicated this man as the proper person to lead an army from his province and the Carolinas against the Spanish in Florida. The old 42nd regiment of foot from Britain and a strong allied Native American contingent, estimated at over a thousand braves, were included in his force of English and colonial soldiers.

With well over two thousand men Oglethorpe descended on north-east Florida, capturing several smaller forts before laying siege to the Castillo de San Marcos itself. On arriving at the fortress, a message was sent to it,

demanding its surrender, only to be returned by the bastion's confident don, who told Oglethorpe he'd be glad to shake his hand inside the castle, if he could make in that is.

An intense bombardment of the place availed Oglethorpe nothing. In addition, his Native American contingent deserted after he called them "barbarous dogs" for proudly bringing him an enemy scalp. Also, the Castillo's commander, during the lengthy exchange of fierce hot shot over many days, sent forth a band of African American militia and Spanish regulars to re-take the first free black settlement in America, Fort Mose. In this they were successful, after a brief but savage firefight against its surprised but battling Scots Highlander garrison from Darien, Georgia.

With these set-backs and his reluctance to storm the seemingly impregnable walls of the fort, having little faith left in the espirit de corps of his colonial soldiers, General Oglethorpe was left no choice but to raise the siege and ignominiously retreat back to Georgia. There he was regaled for his shortcomings on the campaign but has since been redeemed by some historians over the failed expedition.

LATE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY TO MID- NINETEENTH CENTURY

After the French and Indian War, Florida passed into the possession of England. This came about as a result of the Spanish unwisely allying with France in 1761. Between the end of that war and 1771, Scotsman James Grant became governor of East Florida. Grant oversaw a rambunctious and rowdy St. Augustine during his tenure. A visitor later wrote of the place at this time, "Luxury and debauchery reigned amidst scarcity..." Governor Grant returned to England green-gilled and gouty.

The British renamed St. Augustine's castle Fort St. Mark. The Brits maintained a lack-a-daisical post until the outbreak of the colonists' revolution for independence roused them to action, which included beefing-up the castle's armaments and security.. During the conflict the place was mainly used for imprisoning enemy combatants, as well as being used as a base for raids into the southern hinterlands on occasion.

The Spanish crown allied with the freedom- fighting American people in 1779, and thus were able to regain possession of the fort and Florida in 1784 after the Treaty of Paris. Unfortunately, as the decades wore on, border disputes and other incidents like the ferocious Creek Indian Red Stick War, that saw Andrew Jackson invade West Florida, caused much rancor and misunderstandings between Spain and the U.S. government.

So much contention now occurred between the two countries, including Spain's attempt to hold onto a rebelling Mexico, that in 1819, all of Florida was ceded back to the United States with the Adams-Onis Treaty. The Americans began occupying the territory in 1821, renaming the castle Fort Marion, in honor of the crafty Revolutionary War hero, Francis "the Swamp Fox" Marion.

A famous personage from the Americans' stewardship of the Castillo at a later period, was the Seminole chief Wildcat, or Coacoochee. Under a white flag of truce he and some followers were taken prisoner at a parley during the Second Seminole War and imprisoned in the fortress. These 19 Seminoles, which included some women, later made a seemingly impossible and hair-breadth escape from the cell since called Coacoochee's Cell.

The British renamed St. Augustine's castle Fort St. Mark. The Brits maintained a lack-a-daisical post until the outbreak of the colonists' revolution for independence roused them to action, which included beefing-up the castle's armaments and security.. During the conflict the place was mainly used for imprisoning enemy combatants, as well as being used as a base for raids into the southern hinterlands on occasion.

The Spanish crown allied with the freedom- fighting American people in 1779, and thus were able to regain possession of the fort and Florida in 1784 after the Treaty of Paris. Unfortunately, as the decades wore on, border disputes and other incidents like the ferocious Creek Indian Red Stick War, that saw Andrew Jackson invade West Florida, caused much rancor and misunderstandings between Spain and the U.S. government.

So much contention now occurred between the two countries, including Spain's attempt to hold onto a rebelling Mexico, that in 1819, all of Florida was ceded back to the United States with the Adams-Onis Treaty. The Americans began occupying the territory in 1821, renaming the castle Fort Marion, in honor of the crafty Revolutionary War hero, Francis "the Swamp Fox" Marion.

A famous personage from the Americans' stewardship of the Castillo at a later period, was the Seminole chief Wildcat, or Coacoochee. Under a white flag of truce he and some followers were taken prisoner at a parley during the Second Seminole War and imprisoned in the fortress. These 19 Seminoles, which included some women, later made a seemingly impossible and hair-breadth escape from the cell since called Coacoochee's Cell.

| CIVIL WAR PERIOD Early in 1861 Florida joined her seceding sister states in forming the Confederacy. As the Federal garrison withdrew from Fort Marion, Floridian forces marched right in, only to be confronted by one man the departing bluecoats had left behind. He defied the new owners until handed a receipt for the building. A humorous incident right before the war began, that would be sorely missed as the conflict progressed and became so much more than just a sanguinary affair. St. Augustine and its fortress were re-taken by Union forces in March of 1862. From this area of northern Florida many raids and expeditions were launched into the mainland. The most notable being Federal general Truman Seymour's bloodily repulsed attempt to take the state capitol of Tallahassee in Feb. 1864. |

LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY AND BEYOND

In the 1870s the fort was supervised by one Richard Henry Pratt and became one of the chief places Native American prisoners from out west were sent. Many of these people were from the Cheyenne tribe and later, even Apache war leaders like Geronimo and Chatto. Pratt appears to have been an enlightened and progressive man and did much to improve the castle and, he sought to make the charges in his care lives better as well.

He did this by teaching them English and other skills that would help ease their assimilation into society. Right or wrong, at least he did what he thought was best for them. In the future, such advancements in this direction were made, that the government sponsored over two-dozen Native American boarding schools for the tribes, and, allowed churches to open more than four-hundred and fifty other such establishments themselves.

The fort was finally designated a National Monument in 1924. The National Park Service took over in 1933 and, in 1942, the castle was renamed the Castillo de San Marcos in honor of its original Spanish builders. As of 1966 and up until today, it is on the list of National Register of Historic Places, and how rightfully so.

St. Augustine is a very historic and laid-back town with a beautiful white sand beach. The Castillo is certainly one of its major stand-outs and well worth visiting should one be in the north Florida area. Directions there, hours, places of interest, lodging, eateries, etc. can easily be found on the web and elsewhere.

In the 1870s the fort was supervised by one Richard Henry Pratt and became one of the chief places Native American prisoners from out west were sent. Many of these people were from the Cheyenne tribe and later, even Apache war leaders like Geronimo and Chatto. Pratt appears to have been an enlightened and progressive man and did much to improve the castle and, he sought to make the charges in his care lives better as well.

He did this by teaching them English and other skills that would help ease their assimilation into society. Right or wrong, at least he did what he thought was best for them. In the future, such advancements in this direction were made, that the government sponsored over two-dozen Native American boarding schools for the tribes, and, allowed churches to open more than four-hundred and fifty other such establishments themselves.

The fort was finally designated a National Monument in 1924. The National Park Service took over in 1933 and, in 1942, the castle was renamed the Castillo de San Marcos in honor of its original Spanish builders. As of 1966 and up until today, it is on the list of National Register of Historic Places, and how rightfully so.

St. Augustine is a very historic and laid-back town with a beautiful white sand beach. The Castillo is certainly one of its major stand-outs and well worth visiting should one be in the north Florida area. Directions there, hours, places of interest, lodging, eateries, etc. can easily be found on the web and elsewhere.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed