COLONIAL BRUNSWICK

BRUNSWICK TOWN'S FOUNDING IN THE 1700s

Cannon recovered from the river in the 1980s thought to be from the Spanish war ship Fortuna. The vessel blew up in the Cape Fear when the townsfolk retook the port.

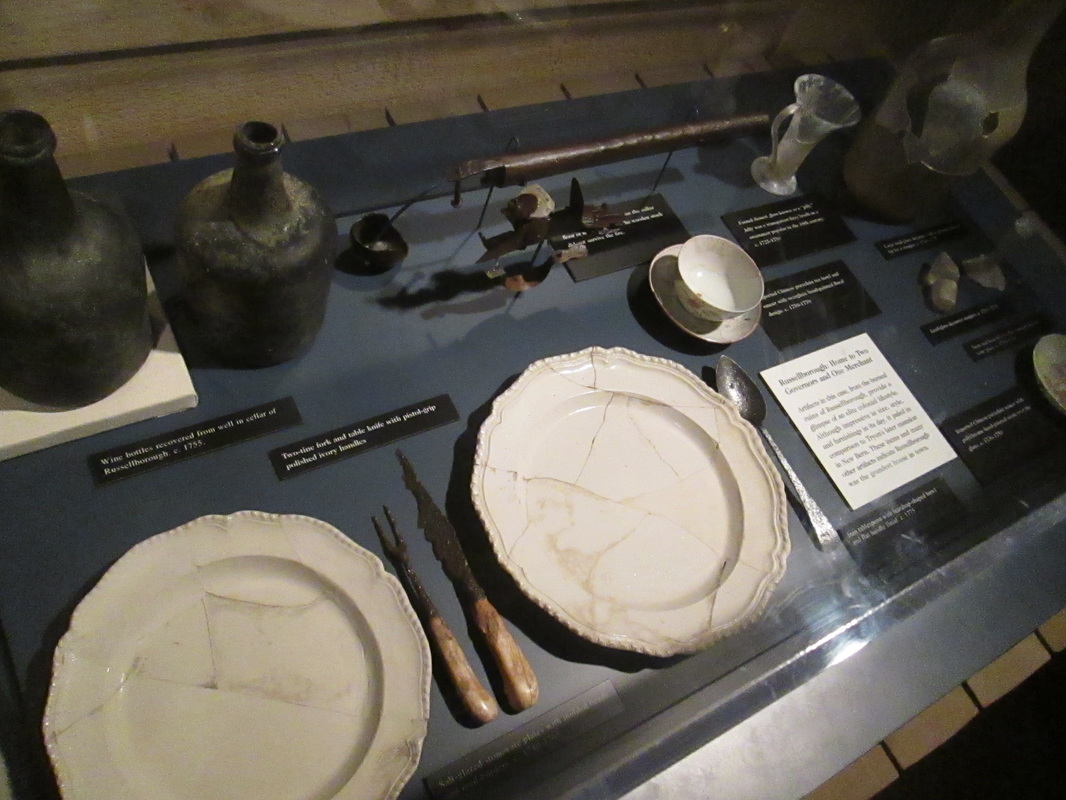

Cannon recovered from the river in the 1980s thought to be from the Spanish war ship Fortuna. The vessel blew up in the Cape Fear when the townsfolk retook the port. Brunswick Town was founded as an important port town in the long ago year of 1726, by one Maurice Moore, the son of South Carolina's governor. The son would have been hard-pressed to find a more bucolic and enchanting spot than right there, about 12 miles up the Cape Fear River on its left side. The king of England at the time was George I, who had originally hailed from Brunswick, Germany, and thus, this early port settlement in Carolina was named after him.

This must have been a generally happy and productive site to live on, as the place was a busy transporting area for the ubiquitous tree products of tar, turpentine, and pitch. The coastal soil was probably good for growing vegetables and fruits, the forests still held wild game in abundance and most probably there were domesticated animals as well. As things went for newcomers to this particular spot on coastal Carolina in the early 1700s, at times it might have been a veritable paradise in certain respects. With even a cooling breeze in the steamy summer months. Walking it today, one can still get this feeling of contentment via the breeze and shade.

With a couple of royal governors living in Brunswick one after the other, the town became a meeting place for the colonial assembly at times in its courthouse. Through and for the Crown back in England, merchants had to pony-up with taxes and shipping expenses to the old Mother Country. However, come the year 1765 the colonists strongly expressed their displeasure about these burdens, especially towards the despised tax stamps that were distributed. So vehement were they in this that they actually got the stamps stopped.

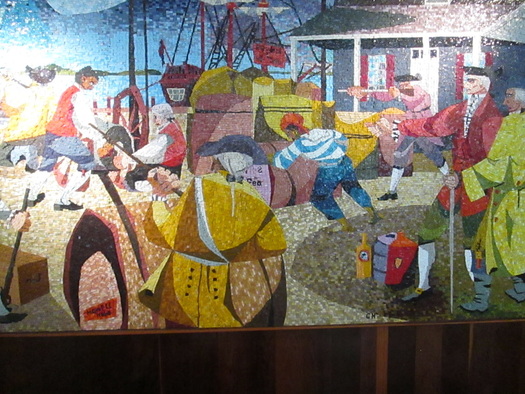

The town began to go down hill as an important place not long after the royal governor relocated to New Bern, and Wilmington to the north started to take on added significance and growth. The War of Jenkin's Ear, that later segued way into the War of the Austrian Succession in Europe, probably didn't help matters any, either. This conflict was a world wide one and Britain and Spain found themselves on opposite sides of the belligerents. The huge mural in the museum shows a microcosm of that war with Spanish ships attacking Brits starting to fire back from the dock.

This must have been a generally happy and productive site to live on, as the place was a busy transporting area for the ubiquitous tree products of tar, turpentine, and pitch. The coastal soil was probably good for growing vegetables and fruits, the forests still held wild game in abundance and most probably there were domesticated animals as well. As things went for newcomers to this particular spot on coastal Carolina in the early 1700s, at times it might have been a veritable paradise in certain respects. With even a cooling breeze in the steamy summer months. Walking it today, one can still get this feeling of contentment via the breeze and shade.

With a couple of royal governors living in Brunswick one after the other, the town became a meeting place for the colonial assembly at times in its courthouse. Through and for the Crown back in England, merchants had to pony-up with taxes and shipping expenses to the old Mother Country. However, come the year 1765 the colonists strongly expressed their displeasure about these burdens, especially towards the despised tax stamps that were distributed. So vehement were they in this that they actually got the stamps stopped.

The town began to go down hill as an important place not long after the royal governor relocated to New Bern, and Wilmington to the north started to take on added significance and growth. The War of Jenkin's Ear, that later segued way into the War of the Austrian Succession in Europe, probably didn't help matters any, either. This conflict was a world wide one and Britain and Spain found themselves on opposite sides of the belligerents. The huge mural in the museum shows a microcosm of that war with Spanish ships attacking Brits starting to fire back from the dock.

A friendly pirate figure in the museum's lobby.

A friendly pirate figure in the museum's lobby. The three photos above are what's left of St. Phillips Church. It's the tallest standing structure at the Historic Site. It took a long time to build this house of worship, not being completely finished until 1768. It was very well made structure that was only in use for eight short years before being burned by the British in 1776. I will tell the reader that it's the best, or rather, most complete church structure that was burned during the Revolutionary and/or Civil War era that I've ever seen in the Carolinas. Anyone who visits this historic house of worship should be delighted, not only with its preservation, but with the very ambience it exudes.

Below are some photos of graves and foundations

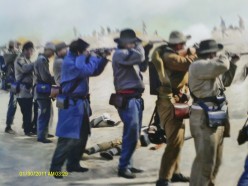

FORT ANDERSON IN THE CIVIL WAR

At the beginning of the war the Southern Government deemed it necessary to build or confiscate a number of forts along the Cape Fear River to aid in defending the important port town of Wilmington. Anderson was about 15 miles upriver from the coast and the mounds you see in the photos here were parts of that labor-intensive construction begun at the start of the war by the South. The two batteries with about 10 guns in total, not only protected vital

Wilmington proper, but gave cover to blockade runners on the river as well.

On December the 20th of 1864, for the second and last time. Robert E. Lee dispatched General Robert Hoke's division from his besieged army to North Carolina for the difficult mission of protecting the indispensable port city, known as the "Gibraltar of the Confederacy". His force was to initially, along with its sparse, but tough

garrison, defend Fort Fisher. These Carolinian and Georgian soldiers entrenched north of the fort on Jan. the 15th as the vast Union armada made its lodgments of soldiers and marines. General Braxton Bragg prevented Hoke

from attacking, which if he had, might have turned the bloody close-in struggle for the place into a victory for the

rebels, despite unarguably taking heavy casualties from the federal soldiers and navy while doing so.

After the fiasco at Ft. Fisher Bragg decided to defend to defend Wilmington upriver. To do that, he put Hoke's

men and others in the two abandoned forts of Ft. Anderson and Sugar Loaf. The young Major-General

posted Kirkland's brigade and the Junior and Senior Reserves around the big sand and wood dune constructions. Other forces from hisdivision manned lines to the east and west. For the following three-weeks he fortified things and kept his troops morale up as best he could.

Despite all his diligent efforts, and for a myriad of problems such as gunboat bombardments and a heavy and

determined attack on his left flank, Hoke ordered Hagood's South Carolina brigade to evacuate Ft. Anderson on

Feb. the 19th 1865. His division then continued its defense of Wilmington from other positions, but the situation

was dire and Wilmington fell on Feb. the 22nd. But not before General Hoke had successfully evacuated essential

supplies, prisoners, and most importantly, his fighting men.

| The site really is a marvelous disc0very. It's intimate, doesn't take all day to see everything, and the trails are great. The museum is friendly with lots to enjoy. Saw this comment there too: Better than Fort Fisher! | Here is a link to a more detailed history (including that since the Civil War, plus the archeology of the site, maps and directions, hours of operation, etc: http://www.nchistoricsites.org/brunswic/brunswic.htm |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed