what's the price of heroes? ~REM

Dedicated to the Gettysburg National Military Park and the descendants and relatives of Generals Hoke and Ramseur

"Major tell my father I died with my face to the enemy." ~ I.E.Avery

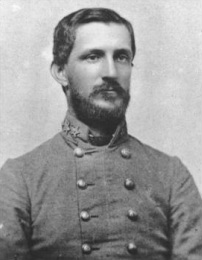

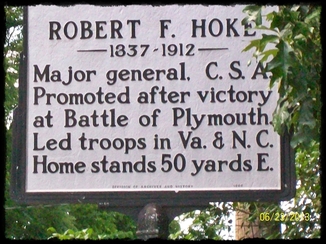

Robert Frederick Hoke

| Avery's brigade of nine hundred men quickly came to attention that 2nd day of July at Gettysburg ready to attack Cemetery Hill. Colonel Avery was riding Colonel Robert Hoke's large and faithful war-horse, Old Joe. He was in command that fateful evening of Hoke's Brigade as the usual leader of the unit, Hoke himself, was convalescing after being wounded at the previous battle in May at Chancellorsville. It was a good thing Hoke was absent as he probably would have fallen like his replacement I.E. Avery did. As can be seen at the beginning of the story, the brave Avery wrote his final words on a scrap of paper. He certainly did die with his face to the enemy; stoically till unconsciousness, hours later in a makeshift hospital behind the lines. |

North Carolina also happened to have had one of the last state legislatures to approve an ordinance of secession from the Union. It can be said with some accuracy, to have been a torn state on whether to secede or not, and remained so throughout the war in certain places, particularly the mountains and a couple of mid-state counties largely settled by Moravian and Quaker pacifist- leaning religious folk.

Robert and his friends, like future general Dodson Ramseur, enjoyed the fields and woods all about, especially the Revolutionary Battleground of Ramsour's Mill. (That story is on Once Upon a History and was an honor to write about.)

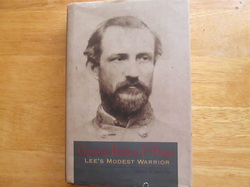

Robert Hoke is one of the lesser known generals of the Civil War, as he never attempted to capitalize on his fame during the years after the end of the conflict. Many others did do so by newspaper articles, books and memoirs, and back and forth arguments on battle strategy's, wrong decisions and right decisions; by generals such as Longstreet, Early, and Pickett for the South, and men like Meade, O.O. Howard, and Sickles for the North; just to name several high-ranking vets who stirred things up between themselves and others over the years after the war. Which also kept their names in front of the public through the newspapers and the time when the personal recollections and histories were initially written for future historians' source material.

Rewarded for outstanding service ...

Civil War historians, and Hoke himself, realized, that if given just a day or two more in eastern Carolina, he would have cleared Union forces from the state at New Bern, returning all its resources to the Confederacy. But it was not to be, as his 7,000 men were immediately recalled to protect Richmond after the start of Grant's many- pronged offensive in May of 1864. Hoke's troops were in the vanguard of repulsing General Ben Butler's armies in-between Richmond and Petersburg as Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia battled the massive Federal army elsewhere. His division was then pivotal, with now, nearly 8,000 men, in handing General Grant one of his worst and bloodiest field defeats of the war at Cold Harbor, thus saving Richmond and earning the accolades of the people of the capital, the South in general, and Lee himself. They were also important elements in the First and Second battles of Petersburg, particularly the latter.

Hoke's military war record was generally outstanding and, varied, fighting in the war's first action at Big Bethel, Virginia, to one of the war's last major battles leading his by then much respected veteran division of two North Carolina brigades (which included the brave and hard-fighting, but sometimes scared, teenage Junior Reserves), plus Hagood's South Carolina brigade and Colquitt's Georgia one, at Bentonville, North Carolina. As mentioned previously, he missed the mighty struggle at Gettysburg due to his wounding at the battle of Chancellorsville, perhaps, something that was meant to be as he most likely would have died there leading his, then, brigade. Fate apparently had a different plan in store for this remarkable and beloved American soldier.

Many considered during the war that Robert F. Hoke was thought highly enough by Robert E. Lee to become his protégé during the autumn of 1864. They were certainly close and what an intriguing thought and outstanding achievement to think that Lee might have considered giving command of the Army of Northern Virginia to a man but 27 years old in case of his death or disability. Come the winter, though, Lee reluctantly sent Gen. Hoke's division, certainly one of the finest in his army, to defend Fort Fisher. After that he held up the Yankee advance on Wilmington(where he evacuated crucial supplies on the eve of its fall , delaying the inevitable, but allowing the South to fight on in NC), and later brilliantly led his division in battle at Wise's Forks and Bentonville.

In his later years, Hoke was to take on an almost uncanny resemblance to ole Marse Robert, too, one of the greatest war commanders in history and most venerated by his troops and fellow citizens, including his soldier opponents and many others in the North, and, world-at-large for that matter.

After the surrender of Joe Johnston's army at Bennet's Place in NC to Sherman (almost three weeks after Lee's surrender), Robert returned home to a devastated Lincolnton. Union general Stoneman's cavalry raid and occupation had seen to that in spades. But Hoke returned home with hope. He refused to wallow in melancholy like many others were.

He quickly hitched his faithful war horse Old Joe to the plow and started growing crops on the Hoke's family land. The man also set about to rebuilding his State and the South in general, and even at one point was offered high honors and the governorship of N.C. on a platter, all of which this modest and highly respected Cincinnatus -like man turned down. He later helped rebuild the industry of NC and opened a resort and spring water bottling company near-by to Lincolnton, where he was to live and pass away on July the 12th, 1912.

Hoke was buried with full military honors in Raleigh's Oakwood cemetery. His goal was to leave the war behind and reunite the country and help his State recover during the harsh years of Reconstruction and beyond. Hoke rarely gave newspaper or magazine interviews, never wrote books or a memoir, thus avoiding the second-civil-war of words that went on through the years amongst so many other veterans from both sides.

He married Lydia Ann Maverick Van Wyck in 1869, producing children which included Dr. Michael Hoke, famed pioneer orthopedic surgeon and founder of the Scottish Rite Children's Hospital, one of the five orthopedic consultants in developing the Shriners' Hospital for Children. He was also a close adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in these matters.

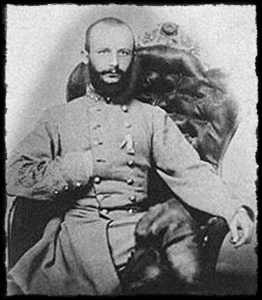

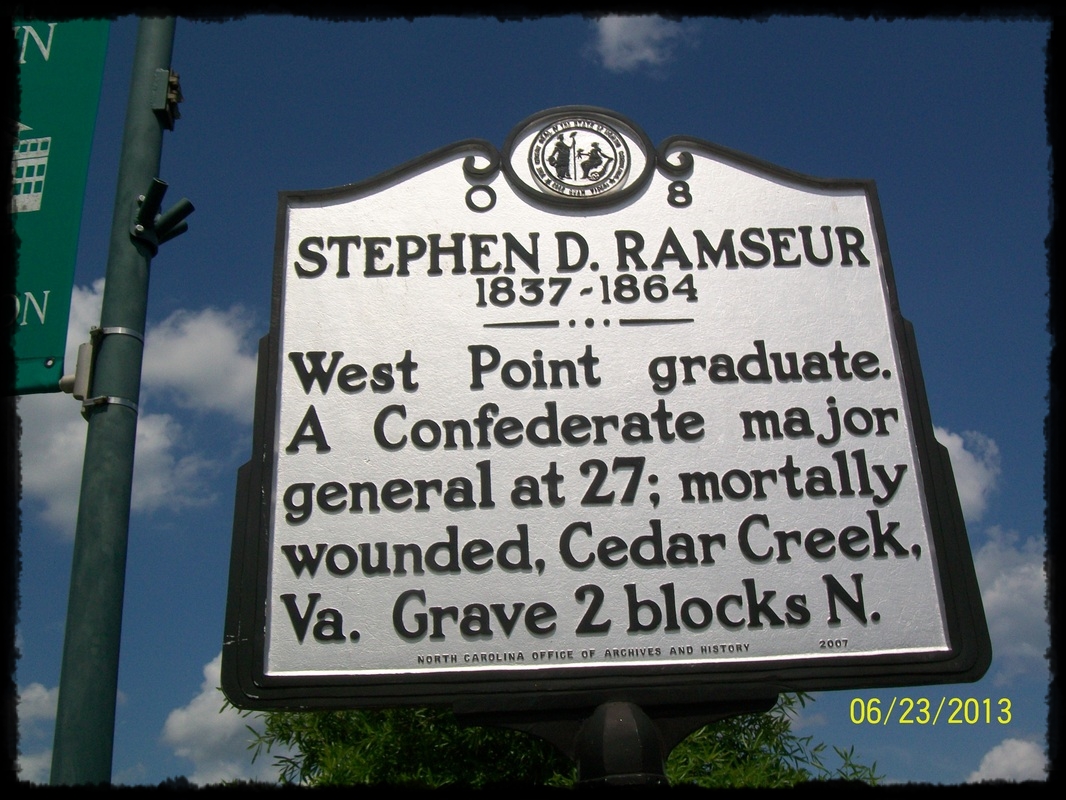

Stephen Dodson Ramseur

| Ramseur graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1860 as a second lieutenant. He was also a close childhood friend of Robert Hoke as mentioned previously. Dodson fought in the 1862 early summer battles called The Seven Days series of battles where he was badly wounded but noticed by General Lee and was also elected by his men the commander of the 49th NC regiment, after which he was sent home to heal. Lincoln County and its environs were where men like these hunted, walked or rode, swam, and learned the ways of nature as boys. In short, it was their land, their heritage, their country. And when the call came to defend it, they answered that call patriotically. |

The small group of elitist lawmakers of the South were mostly large acreage agriculturists, but were still wrong to hold on to the practice of African bondage when others had abandoned it for moral reasons, as well as barely living-wage industrialization and yeomanry farming. And we should also realize it had not been all that many decades before, that the institution ( though fought over at the Articles of Confederation in 1787 & subsequently) had been legal and tolerated in many states outside the South and even countries like France and Great Britain.

Of course places like the New and old England had a much different ratio of whites to blacks, which also factors in when we consider the history of the subject going way back before even the Declaration of Independence, particularly in states like SC and later Mississippi. What is generally unknown is the number of Carolinian's in power positions, like the Laurens, for example, who tried to end the practice starting in the Revolutionary War years. Those who followed in their footsteps were finally defeated in this desire by a small cabal of powerful politicians and plantation owners around the 1830s.

The NC soldiers often grumbled about " a rich man's war and a poor man's fight", but the average Southerner able to bear arms fought for what he considered a direct military threat to his land, his family, neighbors, and constitutional rights. Abraham Lincoln's call for 75,000 volunteers, including some thousands from NC, to put down the rebellion, seemed to seal the deal for succession; not to mention the fact that that would have meant North Carolinian's would be fighting against their fellow southerners if the nicknamed Tar Heel State actually did stay in the Union..

The appellation of Tar Heel is thought to do with NC soldiers tendency to stick to their ranks like they had tar upon their heels. In other words - hard-fighters who tended to bravely hold together, stand fast as it were, in the fiercest battles. An irony, in a sense, because the highest desertion rates also came from NC. And in addition was the fact that one of the state's important industries, for quite some time, had been tar extraction from its many, thick stands of pine trees.

Promoted by the Commander himself

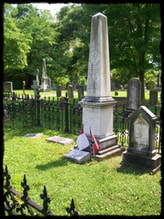

| After the battle at Sharpsburg, or Antietam, the bloodiest single day in American history, Dodson returned to the army recovered from his wound received at the Seven Days' Battle as colonel of the 49th N.C. regiment, only to find himself promoted to brigade command and given his brigadier general's star on Nov. 1st, 1862. At the youthful age of twenty-five, he was the youngest general in the army on that day, which apparently had been promoted by none other than the commanding general of the Army of Northern Virginia himself, Robert E. Lee. In one of the South's greatest victories of the war at Chancellorsville, in May of 1863, Ramseur's, then, brigade, was in the lead of Stonewall Jackson's stun-ning, victorious flanking attack. General Dodson's men were fated to suffer 50% casualties in that very famous surprise assault. Ramseur fought on bravely again at the titanic struggle of Gettysburg, through to the next year's sanguinary two day Battle of The Wilderness, and the following bloody contest on May the 12th, defending the lines at Spotsylvania Courthouse; here he was wounded again but refused to leave the battlefield. Ramseur was promoted to major general and took over Early's division after Spotsylvania, which made him the youngest major general to ever graduate West Point. He fought from there at places like Cold Harbor, against Grant's massive army attempting to take Richmond on the run. And he later followed General Early's small Army of the Shenandoah on its desperate invasion of the North in an attempt to draw off some of the federal army besieging Petersburg and Richmond -- with perhaps a chance at freeing prisoners-of-war at Point Lookout in Maryland or even taking, relatively speaking, a lightly defended Washington City itself. Stephen Dodson Ramseur was to later, bravely, fall mortally wounded with Early's Shenandoah Valley army trying to rally his out-numbered and retreating men in Oct. of 1864 at the battle of Cedar Creek, Va. His remains were sent home for an honored burial. | Ramseur's grave in St. Luke's Episcopal Cemetery, with his wife and child buried beside him. The general's original monument was destroyed during hurricane Hugo. The Daughters of the American Revolution replaced it with the one shown here. |

Photo via wikipedia.org.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed