And if this is your army, why does it go? ~ William Wallace

Driving some parts of Coastal North Carolina are almost like the long, level, and straight stretches of the Great Plains. The main difference of course being the latter place has roads that are much longer and the former has ones that are often through swampy areas, thick woods and other flora.

Indeed, even today near the park, in a car on some of the back roads leading to the site, the isolation can make one feel a part of that time now almost two hundred and forty years ago. Yes, sometimes one can ride several miles in the middle of the day and see nary another vehicle, home, building or person.

As we know through the suffering and death of loved ones, whether they be humans or any other mammal on this earth capable of giving and receiving affection, it is often a more painful experience to experience their travails than our own sufferings. The thought of early demises and deep sorrow must certainly have been on the minds of many friends and family members come the night of February 26th 1776 in the Scottish camps and their communities along and near the upper Cape Fear River.

The next mourning was to bring these forebodings to reality in spades.

Crossroads near the scene of action

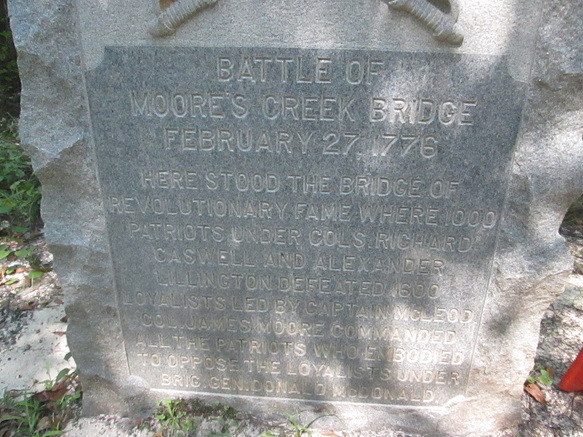

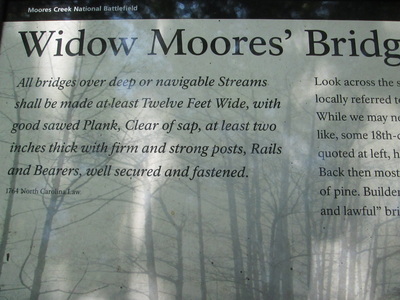

Crossroads near the scene of action The Revolutionary War in America had been raging for almost a year before the Battle at Moore's Creek Bridge occurred in North Carolina, nearly twenty miles north of the colonial port town of Wilmington. So far, the southern portion of the thirteen colonies had mostly escaped any fighting. Whatever had happened in that vein, however, was to swiftly change into something a good bit more serious come the morning hours of February the 27th 1776.

A GATHERING Of SCOTS

It must have been magnificent, like something out of the movie Braveheart, with Mel Gibson as William Wallace

riding back and forth in front of his Scots army at the Battle of Stirling Bridge, inspiring them for the victory to come against King Edward I's overconfident earls and their army of heavy horse, footmen and archers..

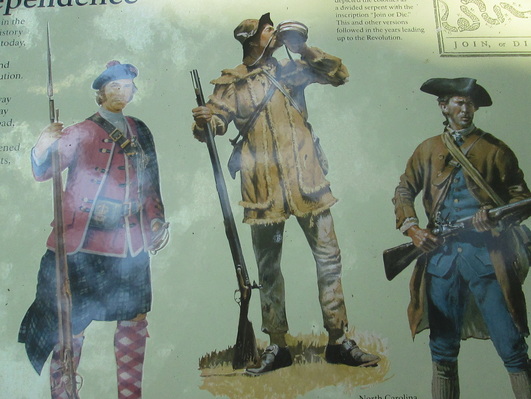

A similar scene presented itself in the middle of February 1776 at Cross Creek, N.C., where the city of Fayetteville is now. The scene has a mature lass and mother named Flora McDonald, riding back and forth, on a great white charger, in front of some 1600 transplanted Highlanders, largely out-fitted in their bagpipes, trews and kilts,

urging them on to battle and to be faithful to king and country.

This action by the inspiring woman was certainly meant, as Flora and her husband Alan, had a new home on the upper reaches of the Cape Fear River that remained loyal to the British Empire. There were still many such insular communities at this time. She and Alan had emigrated out of Scotland to this area right after the war had begun, causing concern for members of the port town of New Bern, where they landed, by men of the patriotic North Carolina's Committee of Safety.

Indeed, Flora and Alan were well known loyalist subjects of the British. After the defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie's attempt to put the Stuart line back on the throne by besting King George ll's son the Duke of Cumberland at Culloden, Scotland, in 1746, the girl supposedly did something memorable. Flora hid the Bonnie Prince, who was dressed as a woman, amongst the rocks while dancing what later came to be called the Flora MacDonald's Fancy to divert those seeking his capture.

And even though the Duke was successful at Culloden, his brutal follow-up rampaging throughout Scotland, allowing his victorious but vicious army to rape and kill at will, forever dashed any chance he had of gaining the kingship himself, which was to go the son of his elder brother George lll in 1760.

However, well before the time of the Battle at Moore's Creek Bridge, Flora and her powerful clan had reconciled with the Hanoverian crown and whatever King George sat upon its thrown. In fact, it is doubtful any more faithful to the monarchy could be found in North Carolina at the time then than the MacDonalds and a few others in the Highland Scot communities residing in the eastern half of the state. However, the Scotch-Irish in the western half of North Carolina and the Watuagan settlements of what later became the northeastern part of Tennessee , were often a different matter altogether.

The March of the Highlander

Earlier in 1776, the N.C. loyalist governor Martin commanded the loyalist militia to gather together in strength to put down any concentration of Patriot fighting forces. But so far as southeastern North Carolina went, the freedom-seeking fighters mobilized effectively enough to prevent those wanting to thwart their desires from concentrating against them in serious battle, at least through 1775, that is.

Scots Approach Bridge

Scots Approach Bridge Over the next several days they were joined by a couple hundred militia, or minutemen as they were known then, several more regulars and basically, men straight off the farms and from the villages. A formidable and determined set of soldiers they were to be sure.

At this time the royal governor passed onto to Moore a proclamation imploring him to join the loyalists ranks. Colonel Moore replied back to Martin with a copy of the North Carolina Test Oath which advised avoiding any effusion of blood by joining the Patriot forces.

Unsurprisingly, neither accepted the others' proposal.

Before the Declaration of Independence was ratified in Philadelphia in June of 1776, the conflict had raged for over a year. Most of the fighting had been done in the North-- not in the lower half of the thirteen colonies. Prior to this date there had been a few minor dust-up's in the South between those seeking self-rule and those beholden to the Crown, including the larger contest at Moore's Creek.

In that same month of June 1776, a British fleet was repulsed trying to enter Charleston's harbor by the stalwart defenders on Sullivan's Island. As a matter of fact, the first declaration concerning independence may had been signed in the village of Charlotte Town, North Carolina, declaring the county of Mecklenburg free on the 20th of 1775, some 13 months before the main one was in Pennsylvania.

There have been disputes on this actually taking place with that first declaration but the preponderance of evidence does seem to support it. In any case, when Cornwallis briefly fought for, and occupied the place, for a short period of time before falling back to Winnsboro, SC, to set up his main center of operations, he left calling the Charlotte village and its environs a "A Hornet's Nest of Rebellion". This statement by the general surely says something for the stiff and determined resistance he found there and about.

Come January the 10th, the state's Royal Governor, Martin, called upon the Royalists to rally up and defeat "the most horrid and unnatural rebellion that has been exerted in the ...Provence." Martin went on to call these patriots wicked, traitorous, and calculating. The Highlanders themselves weren't even sure what the Governor meant. Their enthusiasm, at least at first, was somewhat muted as many believed there was no direct threat to their new-found communities. After a while, though, all this changed and enlistments amongst the Scots rose.

After forming some miles from Cross Creek, they elected leader, Flora's husband , Alan, as he had fought at Culloden, albeit with little action in that fight. The real leaders, however, were two Donalds that had marched up Bunker Hill ( Breed's Hill in fact) almost a year earlier with the British. Eventually this band of loyalists gathered somewhere between 1,300 to 1,600 men, including ex- Regulators.

Flora's famous ride back and forth across their ranks must have been inspiring. They surely needed it with only "600 old bad firelocks and a few broadswords" as Flora later wrote. [actually, a count of captured weapons after the battle would show that somewhat more than this number were present.]

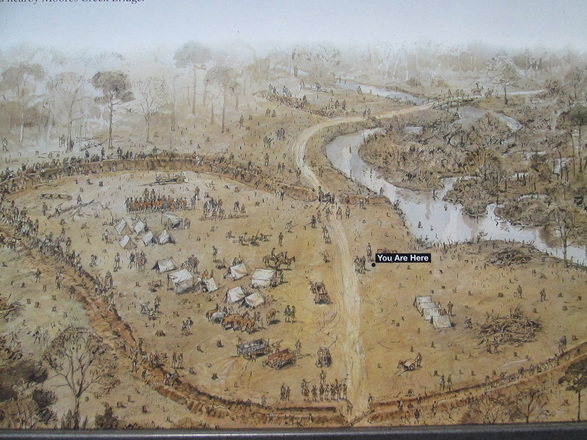

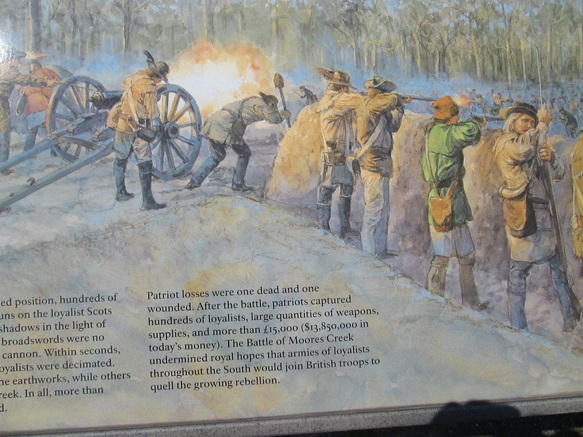

However, Caswell changed his mind after a little while, and ordered the entrenchment work on the west bank to be abandoned. He retired with all his men, over a thousand of them now, to the east bank, the side toward the sea, where he strengthened the defense works Ashe and Lillington had already built and where he mounted his two cannon, which were called , for no reason that endured, Old Mother Covington and Her Daughter.

But, for whatever reason, Caswell decided not to take them on.

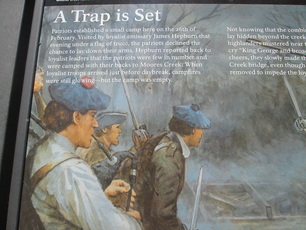

Farther back in the near wilderness the Highlander's officers deliberated. The scouts, who must have been imbibing or blind to an important perception, reported that the entrenchments on the east bank had been left as they were and had not even been filled in, from which they deduced that the patriots had largely retreated. They had heard nothing from the other bank, either, and had glimpsed no fires there. They did not say that a big portion of the bridge was missing in the middle, and apparently had not even noticed that fact.

One of the most determined of these young soldiers was Alexander McLeod, who only the other day had married the daughter of Allan and Flora Macdonald, a teenage girl whom he had literally left at the altar in order to go to war. He offered to lead the advance guard. Captain John Campbell made the same offer. They won their point after throwing out innuendos of cowardice between each other, and the more experienced officers , reluctantly, gave in to their desires.

A first strike force of eighty men was handpicked with great care, armed only with those old bad firelocks and broadswords Flora Macdonald had written about after the battle, along with their smaller dirks. Carrying these weapons of their ancestors, and proudly so, on they went to the sound of bagpipe players marching with them. It surely must have been stirring music for these young men as they proceeded into the unknown.

The bridge was only six miles away. They reached it right before dawn. They now drew their heavy claymore swords, yelled their slogans, or rather, sluagh-gairm war cries from the old country, and charged at speed over the bridge, slowed by the largely missing middle, upon the entrenched and rebellious defenders.

It was magnificent sight to behold but it wasn't war, the result more terrible than anything else in fact.

Two of the Scots leaders got across the bridge but were both felled. When only a few yards from the trenches, McLeod was riddled by at least two dozen birdshot and nine smoothbore balls. Flora Macdonald's husband was captured, and spent a miserable existence in jail until being released in a prisoner exchange at a much later date.

A pursuit by the Patriots after the running enemy might have availed them much, but, for whatever reason, none was attempted. The next morning, however, on arriving at the Moore's Creek Bridge, Colonel Moore did just that and was wildly successful. The Highlanders were, for the most part, rather new to Carolina, and so had bunched together in groups rather than take their chances on the unknown terrain, which included swamps and tangled-up woods. These men, when captured, were treated fairly and there were no acts of vengeance, with the rank and file, or non-officers, released after promising not to take up arms again.

It was not to be.

The casualties were very lopsided at Moore's Creek Bridge, with a few soldiers falling killed and wounded out of approximately 1,050 men present on the American side. The Scots suffered far more with perhaps as many as 50 killed, a greater number wounded of whatever fatalities were incurred, and about 850 seized as prisoners of war.

This triumph has often been underestimated in its effects of stifling and tamping down Highlander morale and their war making potential in Eastern North Carolina. After the contest, the Scots stronghold of Cross Creek and the port city of Wilmington, were pretty much all that was left to Britain for the duration of the conflict in the east of North Carolina.. Recruitment to His Majesty's forces certainly fell far short of what was hoped for after this defining early battle in the southern theatre of operations.

In the picture gallery below are some of the memorials in the park, with the one at far right dedicated to Polly Slocum, who rode a horse to the site 65 miles away from her cabin to aid any wounded or injured Patriots. Perhaps with the dearth of her sides injured men, she showed mercy and assisted the wounded Highlanders.

The park's walk is short, or rather, condensed, but beautiful and very interesting. It even has that new kind of walking material that makes it easy on the feet and ankles. But beware the pinecones and other tree attachments that might fall on the trail. A friend on the path with me twisted their ankle, albeit slightly, after stepping on a cone, but otherwise it is a very comfortable walk and of much enjoyment and reflection.

Here is a link for directions and such by the park service: http://www.nps.gov/mocr/index.htm

RSS Feed

RSS Feed